The misfortune of more than 320 people who for almost three months were trapped in an area of 25 X 25 m (440m), is one of the great heart-breaking stories of Potchefstroom. It was during the First War of Independence (1880-1881). The event is known as the Siege of the Fort of Potchefstroom and happened between 16 December 1880 and 21 March 1881.

This article is part of my series on the historical sites of Potchefstroom. The Fort and cemetery of those deceased during the Siege, is the oldest declared heritage site in Potchefstroom, declared a National Monument on 9 July 1937.

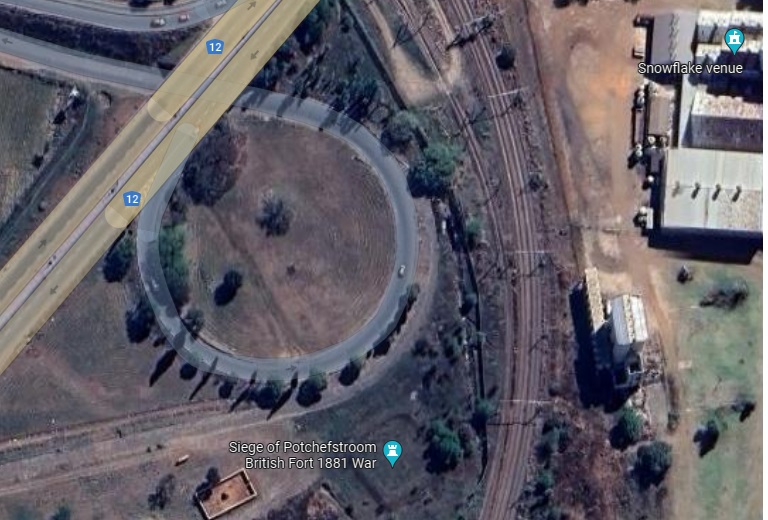

Do not conjure up pictures of a fort similar to the Castle in Cape Town with large stone battlements. The half-finished Fort was just a quadrangle surrounded by embankments when the 320 took refuge there. This embankments are still to be seen, south of the large bridge on the N12 and just across the railway line from the Snowflake Building (which was only built in the 1920s).

The tower of the Potchefstroom Fire Brigade presents an excellent view of the Fort. The embankments indicating where the Fort was are to the left and the walled-in cemetery with memorial to the right. The railway line to Klerksdorp makes a tight turn around the Fort. The initial plan was to lay the railway line over the Fort, but in the 1890s President Kruger vetoed this and decreed that the railway line was to be laid out around the Fort in respect of the events that happened there. See my article about this: https://lenniegouws.co.za/potchefstroom-railway-station-destroyed-by-fire/

This screenshot from Google Maps shows the quadrangle which is the Fort in the bottom middle. To the left of it is the enclosed cemetery. The N12 is clearly visible, as well as the Snowflake Building, just across the railway line. The circle in the middle is the roundabout off-ramp from the N12 into Potchindustria.

Next to the Fort is the enclosed cemetery of the Fort, where those who died during the siege were buried. Inside the cemetery stands a memorial listing the names of all who were buried there. It was erected in 1906. The Fort and cemetery were declared a national monument in 1937. After 1999 it was initially a Grade 1 listed National Heritage Site, but has since then been downgraded to a Grade 2 site. The terrain was archaeologically excavated and researched in the 1970s.

What led to the Siege

The events that lead to the siege of the Fort began in April 1877 when Britain decided to annex the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR) and renamed it the British colony, Transvaal.

Taxes imposed by the colonial government were met with strong resistance. One of those who took umbrage was a man known as Piet “Bontperde” (he used to own piebald horses, hence the name) Bezuidenhout. (Read more about Bezuidenhout at: https://lenniegouws.co.za/street-names-reflect-history-2/ and about the incident at: https://lenniegouws.co.za/jack-borrius-a-man-of-many-adventures/ )

After a group of burgers prevented the sale of Bezuidenhout’s wagon to cover the taxes, the colonial government realized that a rebellion was imminent.

Help was requested from Pretoria and by middle November 1880 a contingent of soldiers with two cannon arrived in Potchefstroom from Rustenburg and Pretoria, the main body existing of two companies of the Royal Scots Fusiliers. A few days later, their commanding officer, Major Thornhill, received instructions to commence with the construction of a fort where soldiers could be housed. He was, however, shortly afterwards, recalled to Pretoria.

His successor, Lieutenant-Colonel RWC Winsloe, arrived in Potchefstroom on Sunday 12 December. He immediately inspected the Fort, but later wrote that it then only consisted of the square surrounded by the embankment. Apparently a picnic atmosphere prevailed at the site and building work only progressed at a snail’s pace.

Lieutenant Colonel RWC Winsloe Photo: Potchefstroom Museum

On 13 December 1880 a protest meeting was convened at Paardekraal near Krugersdorp where the old ZAR were re-instated under the government of the triumvirate Paul Kruger, MW Pretorius and PJ Joubert. See my articles: https://lenniegouws.co.za/street-names-reflect-history-17-missed-streets/ (Paul Kruger), https://lenniegouws.co.za/street-names-reflect-history-8-m-n/ and https://lenniegouws.co.za/smithy-at-the-president-pretorius-museum-collapsed/ (MW Pretorius).

Commandant Piet Cronjé (https://lenniegouws.co.za/street-names-reflect-history-10-p/ ), accompanied by 400 burgers, were sent to Potchefstroom to have the proclamation about the reinstatement of the ZAR printed at the printing house of JP Borrius (see: https://lenniegouws.co.za/jan-borrius-first-government-printer/ ). Cronjé’s instructions were to have the proclamation printed and then leave.

Thornhill saw the approaching burgers on 15 December just after he departed from Potchefstroom by stage coach. He jumped on a horse and raced back to the town to warn the British officials at the magistrate’s office. It then stood directly north of the current Post Office in Greyling Street (OR Tambo). Right next to it, on the corner of Greyling and Wolmarans Street were the Boerenwinkel (Boer Shop).

He then make haste to reach the Fort to warn Winsloe. Within minutes the tents outside the Fort were struck and the two cannon on the two eastern corners of the Fort were manned. Two groups of soldiers were sent to defend the magistrate’s court and the prison. The prison then stood about where the Hall of Central Primary School is today. It was halfway between the Fort and the magistrate’s court and some of the British supplies were stored there.

Later that evening, Chevalier OWA Forssman, one of the richest men in the Transvaal, and his family were persuaded to take refuge in the Fort. The family’s dinner in their house on the corner of Lombard Street (James Moroka) and Church Street (Walter Sisulu), was interrupted. Forssman was under the impression that they would at most have to stay there for a few hours and left with only the clothes they were wearing. They were part of a group of 48 civilians who took refuge there. They were only to leave three months later. (See my article on Forssman: https://lenniegouws.co.za/street-names-reflect-history-4-d-e-and-f/ .)

There is another version of how it came about that the Forssmans were in the Fort. Mrs Elizabeth Russell Cameron, the wife of a Potchefstroom mill-owner, told this later and it was published in an article on samilitaryhistory.org:

A dance took place at the fort the evening before hostilities started. Several of the Potchefstroom ladies, among others Mrs Forssman (wife of Chevalier Forssman) and her daughters attended this ball. When they wanted to return home in the early hours of the morning the burghers prevented them from doing so, and dressed in all their evening finery, there was nothing else for them to do but go back to the camp, where they had to remain for some weeks.

Read my article about the mills of Potchefstroom: https://lenniegouws.co.za/a-fresh-look-at-the-historic-mills-of-potchefstroom/ .

The first shots of the First War of Independence rang out during the morning of 16 December after British soldiers chased after a group of burgers who rode past the Fort. This happened, according to one account in Wolmarans Street, near Nieuwe Street. Another account placed it further east in Wolmarans Street, just west of the crossing with Church Street (Walter Sisulu), where the Rocher house stood (see my article: https://lenniegouws.co.za/street-names-reflect-history-11-r/ ). During this brush one of the burgers were wounded in the shoulder.

Cronjé immediately sent some of his men to the magistrate’s office and the prison. Mrs Cameron remembered:

That morning (the 16th) some women had gone to shop, and, when the British opened fire on the village, they crawled home on all fours in dire fear.

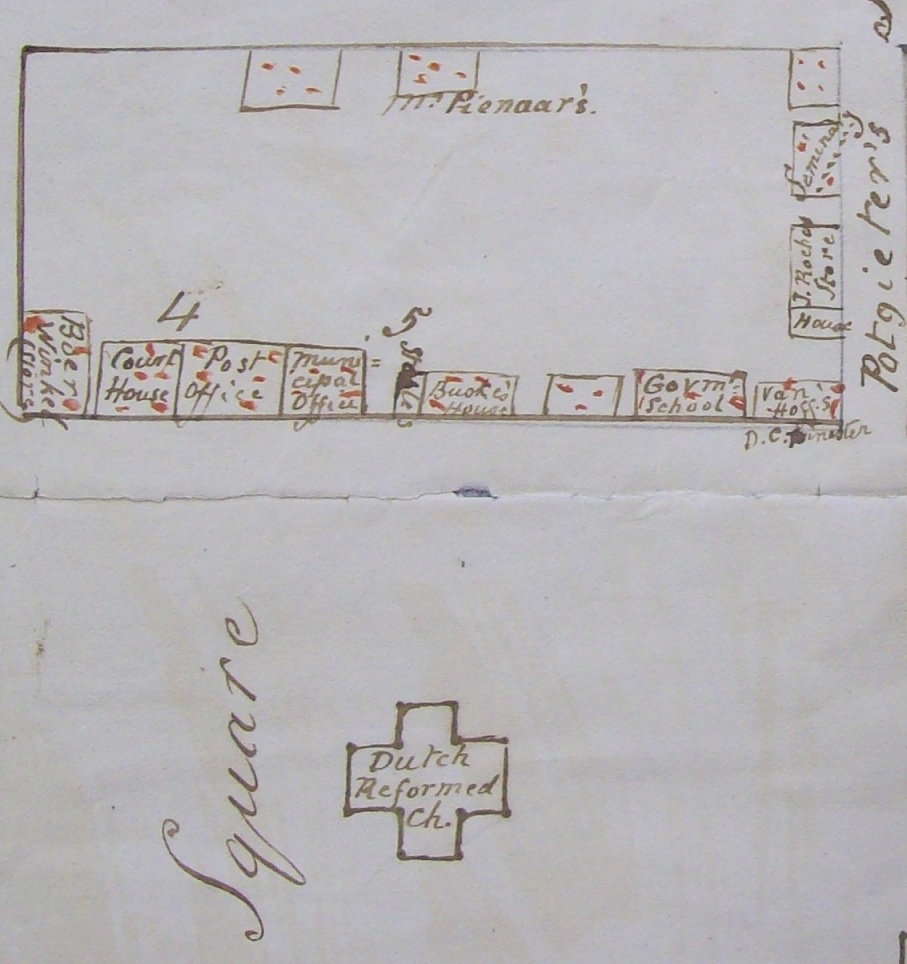

This extract from the Palk map, shows the western façade of Church Square with the Boerenwinkel, the building housing the magistrate’s office, post office and municipal office. North of this building was the house of attorney Buskes (Read more about Buskes, or Buskus in my article: https://lenniegouws.co.za/street-names-reflect-history-2/ .) His wife sympathized with the burgers and assisted them in making what is described as “lampoliebolle”. These were pieces of cloth soaked in paraffin and then set alight and thrown on the thatched roof of the magistrate’s offices. This did not succeed in setting the building alight.

Fighting occurred during the following days. On 18 December Captain AL Falls were killed after he was shot through the door of the magistrate’s office. Major Clarke at the magistrate’s court, immediately signed his surrender. Afterwards it was not necessary for the British to stay at the prison and they vacated it that misty night.

The prison after the Siege. After the British soldiers had vacated the prison, it was occupied by the burgers.

This is how the magistrate’s office looked after the Siege. It also housed the post office (door centre) and the municipal office (door right). The magistrate’s office was at the left of the building and it was through its door that Captain Falls were killed.

This is the top right-hand corner of a map of Potchefstroom drawn by Mrs Anna Palk in 1881 indicating all the important sites of the Siege.

Mrs Palk’s map

Mrs Anna Palk’s map explained much about the Siege and reveals much more about the history of Potchefstroom. The Fort is the square centre left. The “Road to Diamond Fields” at the time was the main road west and was an extension of Wolmarans Street. At the time the railway line did not exist. The “Burial Ground” is the Park Cemetery. Since the current bridge over the railway line was only built in the 1970s, the cemetery was literally a stone’s throw away. Many buildings in Potchefstroom came under gun and cannon fire during the Siege. Mrs Palk marked all the buildings that were damaged with a red dot. Buildings as far as the Royal Hotel (corner of Lombard and Church Streets – James Moroka and Walter Sisulu), were hit, as well as buildings to the east of the market square where the library is today in Gouws Street (Sol Plaatjies). The Palk map is in the collection of the Potchefstroom Museum.

Mrs Anna Sophia Palk (1844-1936) drew the finely executed map which she called “The Plan of Potchefstroom” indicating places of interest pertaining to the Siege of the Fort. The map shows that the Palk residence was in Berg Street (now Peter Mokaba), on the eastern side of the street, just north of Potgieter Street (Nelson Mandela). This puts the house very much at the forefront of the skirmishes. “Dr Palk House” sports five red dots, indicating that the house was caught in the crossfire. On the corner of Potgieter and Berg Street was the neighbouring “Jooste’s church ground” with seven red dots. Rev Jooste of the Dutch Reformed Church sympathized with the British and did not receive much mercy from the burgers when his house burned down. This stood where the Dutch Reformed Church is today on the corner of Potgieter en Kruger Streets (Nelson Mandela and Beyers Naudé). It was the only property that burned down during the Siege.

On 6 January 1881, two spies were caught red-handed by the burgers were summarily executed. One of those was Christian Woite, who practised as a doctor. After being court-martialled, earlier that morning was shot that afternoon at 2 pm. The execution took place behind the Royal Hotel near the river and he was buried in a grave that was dug before his execution. This is according to GF Austen, who kept a diary of the Siege. Prof Willie Prinsloo published an extract in Potchefstroom 150. (See my article: https://lenniegouws.co.za/the-tragic-stories-about-the-early-doctors-of-potchefstroom/ .)

Austen also noted the erratic behaviour of one of the cannon of the burgers, named Grietjie, which caused much mirth in the besieged Fort. Read about Grietjie in my article: https://lenniegouws.co.za/street-names-reflect-history-5-g-h/ .

It was the objective of both the British and the burgers to reach the gunpowder magazine (marked as “2” on Mrs Anna Palk’s map), that stood north of the Fort. Both dug trenches to reach it.

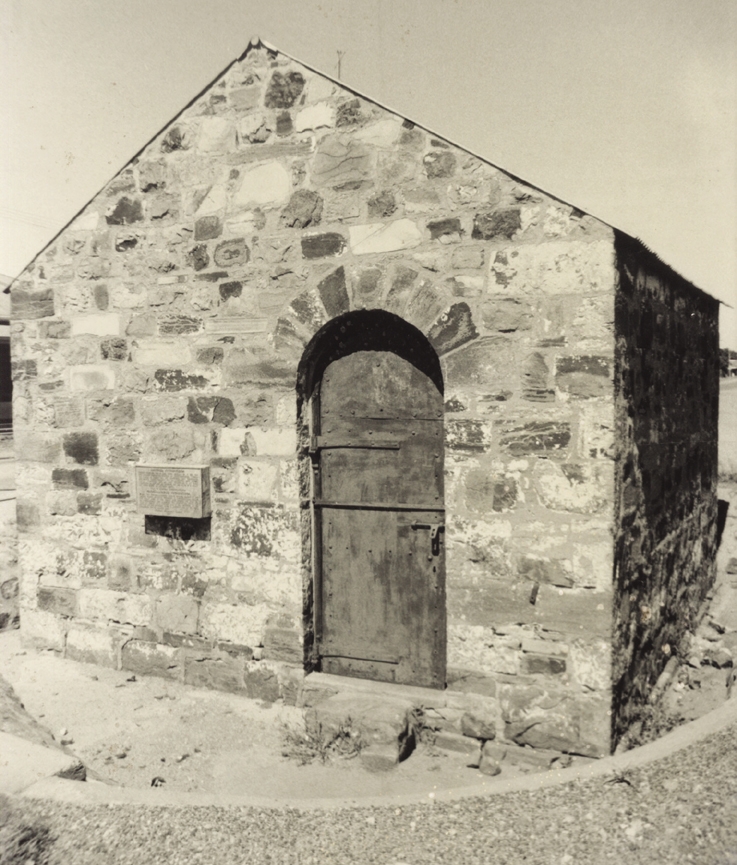

The gunpowder magazine is one of the oldest existing buildings in Potchefstroom. It was built between 1841 and 1863 and still stands next to the on-ramp to the N12 bridge from Potchindustria.

Laughter in the midst of tears

One of the quirky events during the Siege was retold in the 1988 Potchefstroom Herald supplement to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the founding of Potchefstroom:

Whilst digging these trenches to reach the gunpowder magazine a white flag was observed going up in the English trench with a heartfelt request for some tobacco.

The burgers threw a few twists of tobacco in the direction of the British trenches. This opened up the possibility by the burgers for some spying. They bribed a man to spy about what was going on in the Fort.

To soften the hearts of the British, if the spy was caught, twists of tobacco were wound around his body from his neck to his shoes under the clothes.

The so-called “spy” soon spilled the beans about an impending attack from the burgers. He was kept in the Fort and by night was handcuffed to a wagon.

Jenkins quotes Colonel Winsloe in his Story of the Siege of Potchefstroom.

Another cause of irritation for the men was the silence after nightfall because there was nothing to do to divert their attention. A lieutenant of the artillery seemed to feel the silence intensely, and would, on such occasions, crave permission to screech on the parapet, following which would come a terrific volley of rifle fire.

One of the burgers was also riled to quixotic behaviour. He was in the prison when a British bullet went through his ear. The man was so angered that he climbed on the parapet, in full view of the enemy, and shot at the Fort until all his ammunition was gone. His mates expected him to be picked off by a British sharp shooter, but he simply climbed down, unharmed.

A man wanted to cross the Church Square from the corner of Church and Potgieter Streets (Walter Sisulu and Nelson Mandela). He cautiously peered around the corner of the building, but was promptly shot at, the bullet going right through his nose. He was taken to Dr Poortman’s house to be sewn up again.

Dr Poortman’s (see my article: https://lenniegouws.co.za/the-tragic-stories-about-the-early-doctors-of-potchefstroom/ ) house stood at the corner of Kruger and Lombard Streets (Beyers Naudé and Lombard), one of the nearest houses to the Fort. A cannon ball demolished a room in the house and the doctor simply moved his practice to an outbuilding behind the house.

Fort dwellers ate fodder

Conditions in the Fort soon became perilous. The water supply was cut off a few days after the start of the siege. The first well that was dug only produced a little bit of muddy water. A second well, dug on 23 December gave sufficient water. Decades later dark green patches in the grass inside the embankment still indicated where these wells were.

The crates with supplies containing bully beef and rusks were stacked atop the mounds to give more protection. They were soon shot to pieces by the burgers and became rotten. The inhabitants of the Fort were forced to eat rotten sorghum and mealies, intended as horse and cattle feed. Each person received one eighth of a tin of bully beef per day.

Flies and a lack of sanitary facilities caused diarrhoea and dysentery. At the beginning of the siege, the burgers started killing the oxen, mules and horses that were kept in the ditch outside the embankments. According to Lady Bellairs in The Transvaal War, there were initially 76 horses, 121 mules and 137 head of cattle, or 344 in total. Later the rest were released. The rotten carcasses increased the unhygienic circumstances.

Eventually six people died of diseases, including Emily Sketchley, a daughter of OWA Forssman, and Emily’s young brother, Aleric. Read about the well-travelled Dr Sketchley at: https://lenniegouws.co.za/the-tragic-stories-about-the-early-doctors-of-potchefstroom/ .

The three doctors in the Fort helped to contain the number of deaths. They prevented scurvy by having green grass cooked with crushed maize and feeding that to the inhabitants.

Emaciated fort inhabitants entertained in hotel

Winsloe raised the white flag on 19 March and the Siege was ended on 21 March after discussions with Cronjé. Altogether 27 died during the siege of 95 days and the emaciated group who survived the more than three months in the Fort, were greeted by a guard of honour by the burgers when they left the Fort.

Colonel Winsloe and five of his officers were invited to dine with Commandant Piet Cronjé at the Royal Hotel. All over town the rest of the besieged soldiers were treated to breakfasts, luncheons and picnics by the residents of Potchefstroom.

This is how the Fort appeared after it was evacuated in 1881. The circle indicates where one of the five bell tents stood. After Winsloe’s servant was shot in the forearm one evening before dinner, the arm had to be amputated that night. The doctor obviously needed light and the lighted tent was an easy target for the burgers. In spite of the bullets flying over their heads, the amputation was successfully completed without anybody being hit. Winsloe later said that the tents were shot to shards, so much so that there was not a space of one square inch (2,5 X 2,5 cm) to be found without a bullet hole. Photo: Potchefstroom Museum

The memorial that was erected in 1906 with the names of the people who died during the Siege of the Fort in 1880-1881. Apart from the daughter and son of OWA Forssman, Emily Sketchley and Aleric Forssman, one other civilian died. An unknown soldier also passed away. It would be thought that in such a confined space as the Fort all souls should be accounted for, so how it came about that the corpse of a soldier could not be identified, is an intriguing mystery.

Peace was declared on 23 March 1881. On 3 August the Convention of Pretoria was signed and on 8 August the ZAR were reinstated.

Captain Hugh Baillie, after whom Baillie Park was named, offered to allow the British soldiers to camp out on his farm east of the town, where they stayed until they left Potchefstroom two weeks later. Baillie’s residence stood just off MC Roode Drive, directly west of the turn-off to Roots.

Nobody could be blamed for the fact that the siege lasted so long. On the one hand Cronjé was criticised because he never tried to storm the Fort. Winsloe was of the opinion that he could have done it at any time, but never did. Cronjé felt that it made no sense to put his burgers’ lives in jeopardy in such a manner and his main aim with the siege was the suffering of the inhabitants of the Fort.

On the other hand, Winsloe held out because he was waiting for a force to relieve him, which never arrived.

Later the Fort became a popular place to visit for high-ranking British visitors. In June 1925, the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII, visited the site. At this specific visit the memoirs of Colonel Winsloe that was printed by CV Bate, founder of the Potchefstroom Herald, by the Herald Printers, was presented to the Prince by Bate’s daughter, Lorna.

With the Siege of the Fort, Potchefstroom was pitched into war in the blink of an eye. Julian Orford, in an article on samilitaryhistory.org described it as an interesting and unusual event in British military history. To the inhabitants of Potchefstroom it caused much hardship in the time following the Siege. Ernest Jenkins in Potchefstroom 1838-1938 described it as follows:

Immediately after the 1880-1881 War Potchefstroom was a dead-and-alive place. Many persons left the town and went north, south, east, and west in search of pastures new, wherever the opportunity of making a decent livelihood presented itself.

The fact that the Fort and cemetery were declared National Monuments as early as 1937 showed the importance that the town always held the events of those three months.

Sources:

Anoniem, Eers geskiet dan vrae gevra, Potchefstroom Herald, 23-26 Februarie 1988, p. 23,24.

J Orford, The Siege of Potchefstroom: 16 December 1880 – 21 March 1881, http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol052jo.html, Date of access: 26 February 2024.

G Jenkins, A century of history, the story of Potchefstroom (Potchefstroom, 1938), p 66-76.

G van den Bergh, 24 Veldslae en slagvelde van die Noordwes Provinsie (Potchefstroom, 1997), p. 28-40.

RWC Winsloe, The Siege of Potchefstroom, (London, 1896).

WJ Badenhorst & EH Jenkins. Potchefstroom 1838-1938 (Potchefstroom, 1939).

W de Vos, Elizabeth Russell Cameron: reminiscences of an eighty-year old. http://www.samilitaryhistory.org/russl7.html, date of access 12 March 2021.

WJ de V Prinsloo, Potchefstroom 150 (Potchefstroom, 1988), p. 6-10.