Do the residents of Zeederberg Street know that their street was named after a now extinct form of travel? Or that the Weeks family, after whom that street was named, suffered a terrible tragedy? Or that Rev Wynne, after whom that street was named revolutionised building methods in Potchefstroom?

Wallis Street (Central) was named after the assistant of JFI Curlewis in surveying the town in the late 1890’s. TC de Klerk is quite perplexed at why this person was honoured with a street name. One can speculate that they ran out of possible names and decided to use this one. He named another street in the area after his stable hand, Hendrik. (See my article.)

Wandrag Avenue (Central)

was named after a Mr Jan Wandrag who lived in Potchefstroom for many years.

Family suffers terribly tragedy

Weeks Street (South)

The street was named after Captain Andries Johannes Weeks, who was the superintendent of the Location to the south of town. The Location was the designated area where people of colour lived at the time.

Capt Weeks passed away in September 1945 at the age of 66 years while he was still in the service of the municipality.

This was a scant three years after the family had suffered a tragic loss during the Second World War. This was brought to my attention by Mr Pat Page in an email I received in 2013. He grew up in Potchefstroom where is father worked at the Agricultural College and his wife, Marion, was the daughter of a long-time editor of the Potchefstroom Herald, Ernest Jenkins. Pat wrote:

When you visited the cemetery I wonder if you came across the graves of two brothers named Andrew and Walter Weeks, who were both in the SA Air Force and were both killed in air crashes and were buried in the Potchefstroom cemetery. It must have been between 1940 and 1942. They were the ‘laat lammetjies’ of Mr Weeks, the superintendent of the Location at the bottom of King Edward/Kerk Street. Walter, we called him ‘Puggy’, went through school with me and was a close friend. A terrible incident happened when the body was sent by train to Potchefstroom. His father was asked to pay the railage (railway charges) to release the body, but did not have the money. As if it wasn’t enough that he had lost a second son! So friends rallied round and paid the railage. I remember going to the funeral. It was harrowing.

Altogether six boys who were in my class at school and a teacher, lost their lives in the War, as well as three others I knew, but were not in my class.

The Burial Register of the Potchefstroom Cemetery revealed that Andrew Cyril Weeks was 23 years old when he passed away. He was buried on 14 December 1942.

Walter Wheymouth Weeks was 19 years old when he passed away. He was buried on 9 June 1942.

More information was supplied by Mr Frikkie (Douggie) Weeks who is busy researching the family history. He said that the Weeks family are descendants of 1820 Settlers. The patriarch of the Potchefstroom Weeks family was one of two brothers who both had 12 children. Apart from the two brothers who died in World War 2, two of their cousins also passed away in that conflict.

The marble panel in the hall of the Potchefstroom High School for Boys with the names of all its former pupils who passed away during the Second World War. The two Weeks brothers are listed.

Tombstones of the two brothers who passed away in World War 2. Photos: Frikkie Weeks

Williams Street (Baillie Park)

was named after Ivor Knowles-Williams, attorney of Potchefstroom, who was instrumental in the founding of Baillie Park since he acted for the Vyfhoek Development Company. Mr Williams was a partner in the firm Williams, Gaisford and Steyn and was active in the 1940s and 1950s. In 1955 he became one of the shareholders in the company that bought the Potchefstroom Herald from its founder and owner, CV Bate. It was sold in 1960.

This photograph of Mr Ivor Knowles-Williams appeared in the Potchefstroom Herald of 2 August 1957.

Wolmarans Street (Central)

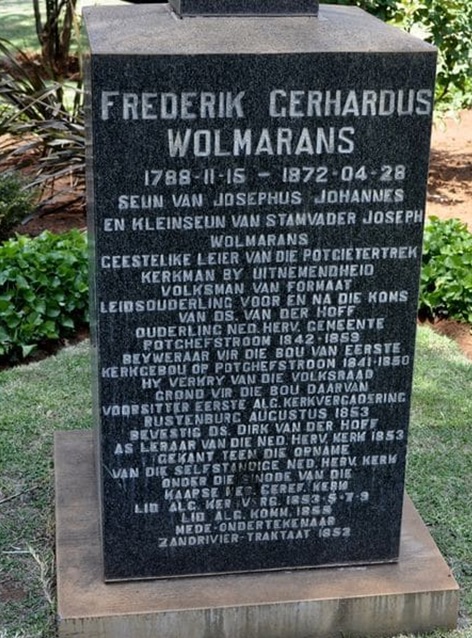

was named after FG Wolmarans (1788-1872). He came to Potchefstroom in 1840 in and in 1853 was the first chairman of the General Church Meeting of the Hervormde Kerk. He inducted Rev Dirk van der Hoff as first minister since no cleric was available. Rev Van der Hoff came to Potchefstroom in May 1853.

This memorial was erected in the garden of the Hervormde Kerk in honour of FG Wolmarans.

Wooden floor is not acceptable

Wynne Street (Baillie Park)

The arrival of Rev W Wynne, a Wesleyan minister, in 1872 is regarded as an important factor in the establishment of a school for English speaking pupils in Potchefstroom. He immediately endeavoured to found a school and on 9 July 1872 the opening of a public day school is announced in the Staats Courant.

In the same year the corner stone of the first Wesleyan Chapel which stood behind the residence of the Goetz family in Church Street (Walter Sisulu) was laid. Today the Impala Hotel occupies the street front of this plot. The corner stone of the chapel was laid on 18 October 1872 by FW Reid. Rose Scorgie wrote in her memoirs that it was the first building in Potchefstroom to have had a wooden floor:

Mention must be made of that which put the old Chapel in the limelight – it was the first building in Potchefstroom to have a wooden floor. The discussions, some quite animated if indeed not heated, about using such scarce and expensive material for people to walk upon, can well be imagined. Said some of the out-of-towners, who came to view this unusual type of floor, ‘It is altogether wrong. Wood should be used only for making wagons, chairs, tables, doors etc.’ In a way their attitude is understandable. In those times flooring and ceiling boards, rafters, joists etc. had to be brought by ship from the Baltic or Oregon and conveyed by ox-wagon all the hundreds of miles up country from the coast. Wood, therefore, was a rather expensive commodity and highly priced.

The Wesleyan Chapel, which stood behind the current Impala Hotel, was laid in 1872 shortly after Rev W Wynne came to Potchefstroom. Photo: Potchefstroom Museum

Traveling by coach is not so romantic

Zeederberg Street (Grimbeekpark)

was named after the Zeederberg coach service which operated from Pretoria, via Johannesburg to Kimberley. The service was founded by CF (Doël) Zeederberg after gold was discovered on the Witwatersrand in 1886. Two other brothers, who operated a transported service from Natal to the Transvaal, later joined the company, but the partnership was dissolved by 1897 and the business again only owned by Doël Zeederberg.

The coaches were imported from America and they transported passengers from Kimberley and Mafeking to Pretoria. Other routes went as far as Bulawayo and Salisbury (Harare) in Zimbabwe.

Julian Orford wrote in the Potchefstroom Herald of 22 August 1975 that the travellers who wanted to travel from Kimberley to the Transvaal had the choice to travel by ox-wagon, light cart or coach.

The latter vehicle seated about twelve persons inside and overflow of from six to eight on its roof. At the rear was “the boot” which was used to accommodate mail, passenger’s luggage and sometimes gold bullion or coin.

The conveyance of bullion left the passengers open to attack by highwaymen and more than one instance is recorded of gold and passenger’ possessions being ‘hijacked’ en route to their destination.

The designers of the seating space available in a coach appeared to have worked on the unlike theory that all passengers, both male and female, were the same width to the beam and only so much space was allowed to travellers inside each vehicle.

The ‘book’ stated that twelve passengers could travel inside and twelve passengers it was to be. There exists the rather delightful story of a well-developed lady who had to be pushed and pulled at the same time, into the coach. Once in, she could not get out and at the end of the journey the door had to be removed before she could emerge.

When the first passenger had taken his or her seat in the coach, succeeding passengers were pushed in, one by one, on alternate sides of the interior, until all space available had been occupied. Then the doors were closed.

Those who remained outside were advised to take their places on the roof.

The whims of South Africa’s seasons are well known. In summer, passengers on the roof either baked or were soaked by sudden downpours and thunderstorms. Lightning was a hazard that could not be ignored and old records tell the story of the driver of the Jubilee Coach who was struck by a bolt of lightning near Ysterspruit.

Then there were tales of mules and mails being swept away by sudden floods and coaches left stranded between flooded rivers. In addition, accidents were not uncommon. Rocks and stones, dug out by the coach wheels, wedged underneath them and sometimes caused the vehicles to tip over or to bounce from pothole to pothole like a demented springhare, much to the discomfort of the passengers and even cause the spokes to break away from the wheels.

In winter passengers froze and arrived at the first staging post swathed in layers of blankets but still numbed by the cold.

Water and food en route were constant problems, which were later relieved to some extent by the erection of stores at some of the staging posts and even a hostel or hotel at the more civilized places.

Most journeys started about 3 am and the coach bowled along, hoping for the best, until the sun rose and lit up the surrounding landscape.

Orford quoted a traveller’s recollection of his journey:

An inside passenger had difficulty in stowing away his feet and when the travellers are packed in, the door is shut. After half an hour limbs become numbed. When a halt is made for change of horses the opportunity is taken of leg-stretching. If the day is warm, the heat of adjacent bodies created a kind of Turkish bath. Sweat is induced and dust adheres to this.

The service was plagued by many problems of which horse-sickness was a substantial problem.

When runderpest (see my article) killed many horses in the Transvaal in 1895, they had zebras trained to draw the coaches. The zebras were trained by a Mr Niek Lottering in the Pietersburg area. This was, however, not really a solution since the zebras were extremely stubborn. They refused to be harnessed after a rest stop and also refused to travel on roads unknown to them. Hence, they were again replaced by horses.

The depot for the service in Potchefstroom was the Royal Hotel on the corner of Church (Walter Sisulu) and Lombard (James Moroka) Streets. Between Johannesburg and Potchefstroom relay horses were available at the Kraalkop Hotel. Geoffrey Jenkins in A Century of History, noted that both establishments were licensed for the convenience of the passengers.

The service was still in operation after the founding of the Union of South Africa in 1910. According to Orford the opening of the railway line to Potchefstroom and later Klerksdorp rang the death knell to the service.

Zeederberg coaches stopped in Potchefstroom at the Royal Hotel. Photo: Beautiful Potchefstroom

Businessman with a heart for the community

Zinn Street (Potchindustria)

The most prominent member of the Zinn family in Potchefstroom is Mr Albert Josua Zinn (1856-1919) who came to Potchefstroom with his father, Wilhelm Gottlieb Zinn (1815-1902). Wilhelm Zinn, from Graaff-Reinet, was appointed as translator in the ZAR in 1864 and came to Potchefstroom. In 1866 he was appointed as auditor general and the family moved to Pretoria. He later resigned, bought the farm Eikenhof at Johannesburg and passed away there.

In an original manuscript, which is in the Archives of the Potchefstroom Museum, a son of Albert Josua Zinn, son of Wilhelm Gottlieb, recounted his father’s life.

Albert came to Potchefstroom as an eight year old. With little schooling he started working at the shop of Read (formerly Pavey and Read)on the corner of Potgieter (Nelson Mandela) and Church (Nelson Mandela) Streets. With 17 clerks this was a large operation and amongst others they packed tobacco which was shipped to Europe and the United Kingdom under the Koedoe brand.

Albert Josua Zinn (1856-1919) Photo: Potchefstroom Museum

He became a manager and when a branch was opened in Johannesburg the other manager managed that shop. Albert Zinn then became a partner in the firm. The family first resided in Berg Street (later Van Riebeeck, now Peter Mokaba). When Albert became a partner they moved into the house behind the Read shop, which fronted on the market square.

Albert Zinn was of good service to the firm. He was bilingual, which made communication with the Boers much easier. They mostly took supplies on account, to be paid after the harvest. Zinn often travelled the length and breadth of the Transvaal to collect outstanding debts.

When Read passed away the firm was liquidated.

Albert Zinn was a community-minded man and often provided fireballs and fireworks to amuse the townspeople on the market square. At Christmas time he provided food parcels to poorer residents.

Zinn loved hunting and on his trips to collect debt, he would shoot much game. The surplus meat was again distributed to poor people. Church functions, before a hall was available, was held in his garden lighted at night by Chinese lanterns.

With his excellent organisational and business skills, he was appointed to manage the commissariat under General Piet Cronjé (see my article). He escaped imprisonment at Magersfontein, fled to Pretoria and Machadodorp with the commissariat and came back to Potchefstroom. Here he was captured by a British commando, who suddenly came to the town. He was betrayed by Hensoppers (Boers who were sympathetic towards the British forces) and sent as a prisoner of war to St Helena.

After the War he became a director in the Algemene Boerenwinkel which stood on the corner of Wolmarans and Greyling (OR Tambo) Streets. He managed the Wilgeboom and Smithfield settlements after the unoccupied land was bought by Hugh Carliss and the settlements created.

When the Alexandra Park Cemetery became full, he was appointed by a Dr Kah to inspect the cemetery and was appointed to organise the enlargement of the cemetery.

For the last 12 years of his life, he worked for the school board, overseeing all the vehicles transporting pupils. He also was inspector of school attendance.

During the second wave of the Spanish Flu in 1919, he visited a few farm schools when he fell ill and passed away on 2 August 1919.

The original source of and inspiration for these articles is a series of 13 columns written by “Senex” for the Potchefstroom Herald on the origins of the street names of Potchefstroom, published from 17 December 1974 to 24 June 1975. Senex was the pseudonym of Mr Jurgens Smith, a long-time teacher at the Potchefstroom High School for Boys. Smith’s primary source of information was the research of Mr TC de Klerk, who studied the origins of the street names of Potchefstroom to write a master’s dissertation in the 1960s. He sadly passed away before completing his studies. Some of De Klerk’s research is kept in the Archives of the Potchefstroom Museum, which otherwise also provided a rich source of information.

Epilogue

This almost concludes my series on the origin of the street names of Potchefstroom, a project that kept me busy for all of this year. This is, however, not the last instalment. I have omitted some street names solely because I did not have any information on their origin at the time I wrote the specific article. Some of this information has now come to light and I will do an article on the missed streets.

With the wide-ranging street name changes in 2006 streets that were formerly named after people who played an important role in the history of Potchefstroom received new names. This does not negate their prominence in the history of the city. Therefore an article on the lost street names will also follow, but only in the new year.